The (Digital) Fine Print

A lot of people don't realize this, but when you pay for an e-book, you're not actually buying it -- you're renting it.

When you go to the bookstore and exchange money for a copy of War and Peace, you become the owner of that hefty paperback. You can lend it to your friends, you can sell it on eBay, you can cut it up and make origami. Simple.

Before Amazon (et al) accepts your lucre in exchange for an e-book of the latest James Paterson emission, you are obliged to accept a EULA -- an End User Licensing Agreement. (It's that endless hunk of legalese you don't read before clicking "I Agree.") Essentially the EULA says that you are paying Amazon for access to the e-book. You can't lend it to anyone without Amazon's permission. You can't sell it to anyone. It's not yours.

This is true for most digital content. There's a big legal difference between buying a Taylor Swift CD and streaming Folklore on Spotify. The companies in control of much of our culture would rather charge you repeatedly for a lease than just once for a purchase. The upside of this arrangement? You can watch/hear/read a vast universe of stuff. The downside? Your "collection" is made of computer code that a mega-congomerate can take away at a moment's notice.

But wait, you say -- if I don't own my digital booty, how come the button I clicked on Amazon said "buy"? Well, that's what Amanda Caudel wants to know. She filed a class action suit in California claiming that Amazon "secretly reserves the right" to take back its movies/books/music, and is generally engaging in false advertising.

Amazon's lawyers replied: It's not our fault you didn't read the fine print, and it wouldn't even matter if you had. "An individual does not need to read an agreement in order to be bound by it," they said.

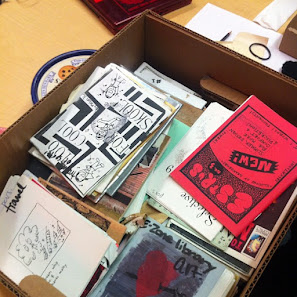

Amazon's argument will almost certainly prevail in court. If you want to build a personal library, something you can keep and hand down to the next generation, you gotta buy books made of paper, not pixels.

Comments

Post a Comment